Being an international seminary student in America, and recently studying the Protestant Reformation in Germany and the more recent history of Christianity in England and America, made me realize how little I know about the details of the reformation in my own country of Finland and how it came about. This led me on a quest to study my own reformation heritage in more detail and learn how it applies to the current spiritual situation of Finland.

The Protestant Reformation in Finland and Sweden

When studying the history of the reformation in Finland, it needs to be noted that in many history books it will be included under the heading of the reformation in Sweden, this is because of Finland being ruled by Sweden (from the 13th century until 1809). It would be correct to conclude that the Finnish reformation followed in many ways the pattern directed by the Swedish crown. But it also needs to be noted that Finland did have a reformation of its own that was in many aspects separate from that of Sweden. Since the details of the Swedish reformation are too many to cover in the scope of this article, I will focus on the distinctively Finnish part of the reformation.

Finnish Men Trained in Wittenberg

The first Finnish reformer has been identified as Petrus Särkilahti, a young Finnish man who studied in Wittenberg, Germany under Luther himself. While in Wittenberg, Särkilahti learned and embraced the newly rediscovered truths of the Bible, which had lain hidden under the rule of the Roman Catholic Church. After finishing his studies in Germany, Särkilahti returned back home to Finland in 1524 and began preaching in the native Finnish language. Many people came to hear him as he publicly proclaimed reformation truth in the Finnish language of the people instead of Latin (which the common people did not understand), but he was soon silenced and his name disappears from the historical records, it is likely that he died sometime around 1528. His time of ministry proved to be very short, but in God’s providence it would later show itself to be a very important beginning of a movement.

Mikael Agricola

One of the young men who were profoundly impacted by the witness of Särkilahti and his preaching of Protestant truth was a man called Mikael Agricola. Agricola was a young clergyman who, following in the footsteps of Särkilahti, also went to study in Wittenberg to learn under Luther and Melanchthon. In God’s providence, the main reason that Agricola was able to go and study in Wittenberg was that the recently appointed Bishop of Turku, Martin Skytte, was financing Agricola’s studies and was very supportive of sending young Finnish men to study in Wittenberg. This is especially noteworthy, when taking into account that even though Bishop Skytte was appointed to his position by the King of Sweden and without Papal approval, he still remained a Roman Catholic himself and never fully embraced the Lutheran teaching of the reformation. It seems that Skytte was a very patient man who had endured a lot of hardship in his life and did not want to cause more controversy, but rather saw the value in supporting the Protestant Reformation even though he did not agree with it all. This decision by Skytte to send young Finnish men to be trained in Wittenberg would prove to be a great advancement for the cause of the reformation in Finland, not just in the case of Agricola, but also for many of the other men (around ten in total) who were sent there to study and would later return to help with the reformation in Finland.

Agricola’s Impact in Finland

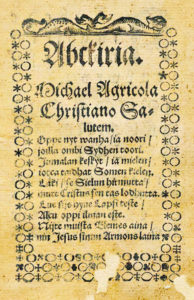

Agricola’s ABC-Book

After finishing his training in Wittenberg, Agricola returned to Finland with a letter of recommendation from Luther and Melanchthon. Soon after his arrival, he was given the position as the rector of the Latin school in Turku, where he worked for the next nine years. During that time he also worked on many of his literary projects, the first one of them being his ABC-Book (published in 1543), which was the first book ever published in the Finnish language. The book was a simple primer to the Finnish language and also included a translation of Luther’s Small Catechism. It is mainly because of this groundbreaking work that Agricola is often referred to as the father of the written Finnish language. The next year (1544) he published another monumental work, a biblical prayer book (900 pages), which included different material from the Bible, church fathers, and the reformers. Above all these, his most important achievement was his translation of the New Testament into the Finnish language, which was published in 1548. Agricola was convinced of the reformation principle that the word of God should be accessible to the common man in their native language. It was largely due to this literary work that Agricola sought to undertake in obedience to God and for the good of his fellow countrymen, that the reformation was able to get a hold on the Finnish people in a different way as opposed to if it had only come through the forced political rule of the Swedish crown.

After Bishop Skytte died in 1550, Agricola eventually became the officially recognized Bishop of Turku (1544), making him the first Protestant Lutheran Bishop of Finland. Not long after Agricola became Bishop, the war started between Russia and Finland. In order to make a peace treaty, Agricola departed to help in Moscow. After the settlement was made, they returned back to Finland, but on the way Agricola suddenly died in 1557 on the Karelian Isthmus at Kuolemanjärvi (“Death Lake”).

During Agricola’s life-time paganism and Roman Catholicism still competed with the Protestant faith, however by the time of Agricola’s death Lutheranism had already gained a strong hold on the Finnish people and in 1593 Lutheranism was made the official religion of Finland.

Thankfulness for a Legacy

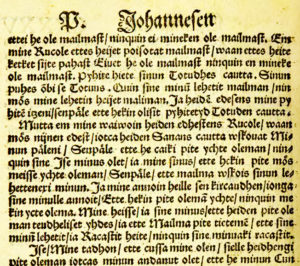

Agricola’s translation of John 17:17

When thinking about my heritage as a Finnish Christian (although not a Lutheran myself, but certainly a Protestant) and how God brought about the Finnish reformation, which in turn gave the Finnish-speaking people the greatest gift on earth–the written Word of God–I am overcome by thankfulness for this legacy and blessing that God has bestowed on Finland. On the other hand, I am saddened by the current situation of Finland, which as a country has again completely rejected God and His Word (even though still on paper claiming to be a ‘Christian’ country). One major lesson that stands out from the work of Agricola, was the great importance that literature–in particular the Word of God, but also other Protestant writings–had in advancing the cause of Christ. The truth of the gospel needs to be made known in the language of the people, and there is still a great need for biblically sound material in the Finnish language.

Was the Finnish reformation finished?

Old church ruin in Finland

Agricola and the others with him certainly completed a great task in helping Finland to turn from Catholicism to the Protestant Lutheran faith. However, the reformation will always have to continue, mainly in the reformation of individual sinners who are converted to Christ, but also in the realm of the Christian church’s understanding of Scripture in how it relates to Christian doctrine and practice. Even though we should rightly be thankful for the giants of the reformation and how God used them to give us a clearer understanding of the gospel, we also need to recognize that there were many areas (such as baptism, ecclesiology, eschatology, etc.) in which their understanding and practices were not fully in accordance with the Word of God. Therefore, the call to any Christian, whether Finnish or any other nationality, is to strive forward and continue the reformation, both in our personal lives as we strive for Christlikeness, and in seeking to bring the truth of the gospel of Christ to those around us. Semper reformanda!

WORKS CONSULTED:

Agrcicola 2007 – juhlavuosi “Mikael Agricola”, accessed June 19, 2015.

Appold, Kenneth G. The Reformation: A Brief History. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

Bergroth, Elis. Suomen Kirkon Historia Pääpiirteissään. Porvoo: W. Söderström, 1892.

Cameron, Euan. The European Reformation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Evans, Robert P. Let Europe Hear: The Spiritual Plight of Europe. Chicago: Moody Press, 1963.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s. v. “Church of Finland”, accessed June 19, 2015.

“Finland.” The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. 15th ed. Vol. 19. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2005.

Grell, Ole Peter. The Scandinavian Reformation: From Evangelical Movement to Institutionalisation of Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Lander, Patricia Slade, and Claudette Charbonneau. The Land and People of Finland. New York: Lippincott, 1990.

Maude, George. Historical Dictionary of Finland. 2nd ed. Lanham: Scarecrow, 2007.

Needham, N. R. 2000 Years of Christ’s Power: Part Two: The Middle Ages. London: Grace Publications Trust, 2000.

Needham, N. R. 2000 Years of Christ’s Power: Part Three: Renaissance and Reformation. London: Grace Publications Trust, 2004.

Pulsiano, Phillip, ed. Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland, 1993.

Rublack, Ulinka. Reformation Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

“Scandinavia: Lutheranism and National Identity.” The Cambridge History of Christianity: World Christianities, C.1815-c.1914. Ed. Sheridan Gilley. Vol. 8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Leave a Reply